Monthly Long-Read: Britain’s Railways at 200 - A Brief History

In 2025, Britain is celebrating 200 years since the advent of the first regular passenger railway. As with most anniversaries like this, Britain is celebrating these two centuries of railway history, with major events across the country, special events at heritage railways, and a panoply of new books and TV shows about Britain’s railways. As I’m a train buff myself, I thought it would be fun to explore the history of Britain’s railway for this month’s featured article long-read. In a future article, I will explore my own experiences on Britain’s rails (I tried to weave them into this article, but it’s already really long!). We will explore how these iron roads transformed a nation, revolutionized travel, and continue to shape the country's landscape and identity. All aboard, folks, this one is a long one!

Introduction: The Rails That Built Britain

The rhythmic clickety-clack of wheels against track, the distant whistle echoing across green valleys, the hiss of steam, and the smell of coal smoke – these sensory touchstones have been woven into the British experience for exactly 200 years. In 1825, when the Stockton and Darlington Railway first opened in northeast England, few could have imagined how profoundly this innovation would reshape not just Britain, but the entire world.

The anniversary marks not merely the birth of a transport system, but the dawn of an era. Britain's railways did more than connect cities; they stitched together a modern nation, democratized travel, accelerated industrialization, standardized time itself, and created entirely new communities. The railway introduced millions to the concept of mass transportation, brought seaside holidays within reach of the working classes, and made possible the modern commuter lifestyle we now take for granted.

Two centuries later, Britain's complex relationship with its railways continues to evolve. From the Victorian era's railway mania to post-war nationalization, from the controversial Beeching cuts to privatization and now to a new era of recovery and reinvention – Britain's railways have repeatedly reflected the nation's changing economic philosophies, social priorities, and technological capabilities.

This anniversary year provides an opportunity not just for celebration, but for reflection on the legacy and future of what might be Britain's most transformative innovation. As we board this journey through 200 years of railway history, we'll explore how these steel arteries pumping through the British landscape have shaped the nation's heart and soul – and consider what the next century of rail travel might bring.

Part I: The Birth of a Revolution (1825-1850)

Coalfields and Visionaries

Britain's railway story begins not with passengers, but with coal. In the northeast of England, the need to transport heavy loads of coal from inland mines to coastal ports had already spawned primitive wooden "wagonways" by the early 18th century – horse-drawn carts running on wooden rails. These early systems, while crude, established the fundamental concept of reducing friction by providing a smooth, guided path for wheeled vehicles.

The crucial technological leap came through a convergence of innovations. The development of steam power, pioneered by Thomas Newcomen and James Watt for pumping water from mines, provided the potential energy source. Improved iron production techniques made possible stronger rails and more durable components. And it was the genius of engineering pioneers like Richard Trevithick, who built the first steam locomotive to run on rails in 1804, that began to combine these elements into something revolutionary.

But the true father of Britain's railway age was George Stephenson. Born to illiterate parents in a mining community, Stephenson was largely self-taught. He constructed his first locomotive, "Blücher," in 1814, and steadily refined his designs over the following decade. When plans emerged to build a railway between Stockton and Darlington to transport coal, Stephenson persuaded the developers to use steam locomotives rather than horses.

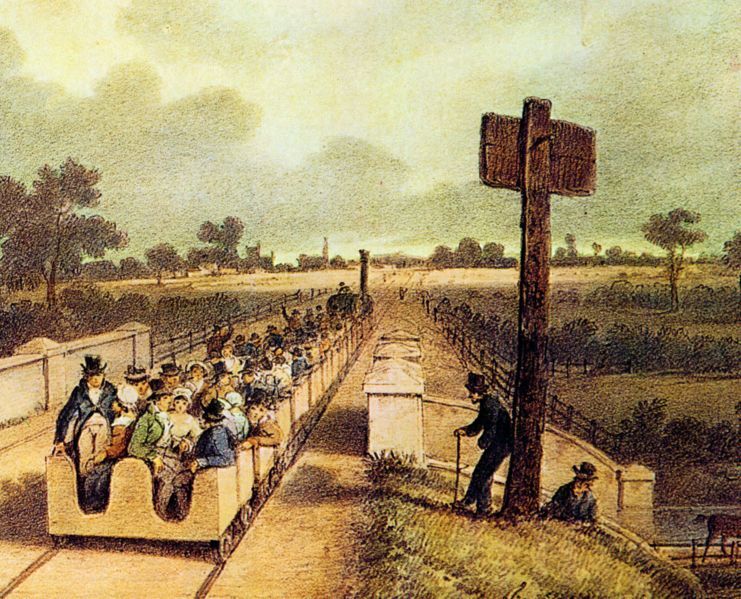

On September 27, 1825, a momentous event unfolded in County Durham. Stephenson's locomotive "Locomotion No. 1" pulled a mixed train of coal wagons and passenger coaches along the newly constructed Stockton and Darlington Railway, inaugurating the world's first public steam railway. Though primarily designed for freight, the railway also carried passengers from its opening day – a hint of the broader social transformation to come.

The significance of this innovation cannot be overstated. Previous forms of land transport moved at the speed of animal power – rarely faster than 10 miles per hour. Suddenly, humans could travel at 15, then 20, then 30 miles per hour – speeds previously unimaginable on land. Time and space began to compress in ways that would fundamentally alter human experience.

If the Stockton and Darlington represented the birth of railways, the Liverpool and Manchester Railway marked their coming of age. Opened in 1830, this line was the first to rely exclusively on steam power, the first to carry passengers as its primary business, and the first to run a regular scheduled service.

Its creation was spurred by commercial necessity. Liverpool's booming port needed better connections to Manchester's textile factories, and the existing canal system was proving inadequate. George Stephenson and his son Robert were appointed as engineers, overcoming tremendous technical challenges including the crossing of Chat Moss, a seemingly impassable peat bog.

The line's opening featured the famous Rainhill Trials, a competition to determine the most suitable locomotive design. The Stephensons' "Rocket," capable of speeds up to 30 mph, emerged triumphant, cementing their place in engineering history. Tragically, the opening ceremony was marred by the death of Liverpool MP William Huskisson, who was struck by Rocket – the world's first widely reported railway fatality.

Despite this inauspicious start, the Liverpool and Manchester Railway proved immensely successful, carrying 445,000 passengers in its first year alone. Its achievements silenced critics and triggered "railway mania" – a period of feverish investment and construction that would lay the foundations of Britain's national network.

Railway Mania: Building a Nation

Between 1830 and 1850, Britain experienced an unprecedented infrastructure boom. Thousands of miles of track were laid, connecting major cities and countless towns and villages. The pace of expansion was breathtaking – in 1830, Britain had just 98 miles of track; by 1850, this had exploded to over 6,000 miles.

This expansion was funded through private enterprise, with hundreds of railway companies forming to build and operate lines. The investment frenzy peaked in the mid-1840s, when Parliament approved 272 new railway acts in a single session. Not all proposed lines were built, and many investors lost fortunes when the speculative bubble burst in 1847, but the essential framework of Britain's railway network was established with remarkable speed.

Key developments during this period included:

- The opening of the London and Birmingham Railway in 1838, engineered by Robert Stephenson, which connected the capital to the industrial Midlands

- Isambard Kingdom Brunel's Great Western Railway, completed in 1841, linking London with Bristol and the southwest

- The development of major railway termini in London, including Euston (1837), Paddington (1838), and King's Cross (1852)

This rapid expansion transformed Britain in countless ways. Cities grew as transportation barriers fell. Industries relocated to leverage new logistics networks. Government mail services accelerated dramatically. And for the first time, ordinary people could travel significant distances for work, family visits, or leisure.

Part II: The Golden Age of Steam (1850-1914)

By the 1850s, Britain's patchwork of competing railway companies had created a chaotic system. Passengers traveling long distances often needed to purchase multiple tickets and change between incompatible services. The Railway Clearing House, established in 1842 but growing in importance during this period, helped standardize practices and allocate revenue between companies when journeys crossed network boundaries.

Gradually, the hundreds of smaller railway companies began to amalgamate into larger, more efficient organizations. By the 1870s, a handful of major companies dominated, including:

- The Great Western Railway (GWR)

- The London and North Western Railway (LNWR)

- The Midland Railway

- The Great Northern Railway

- The North Eastern Railway

- The London, Brighton and South Coast Railway

These companies competed vigorously for passengers, freight, and prestige, driving improvements in comfort, speed, and reliability.

Technical Innovations and Growing Speeds

The Victorian era witnessed continuous technical refinement in railway engineering. Locomotives grew more powerful and efficient. Railway signals evolved from simple flags to complex mechanical systems with fixed signals controlled from signal boxes. The telegraph allowed information to travel ahead of trains, dramatically improving safety and coordination.

Brunel's bold decision to use a broader 7-foot "gauge" (the distance between rails) for his Great Western Railway created superior stability and speed but ultimately lost to the standard 4-foot-8.5-inch gauge used by most companies. By 1892, after the "Battle of the Gauges," Parliament mandated standardization, forcing the GWR to convert its entire network.

Speed became a particular obsession. In 1847, the Great Western's "Iron Duke" locomotives could reach 70 mph. By the early 20th century, new designs like the GWR's "City" class and the London and North Eastern Railway's "Atlantic" locomotives regularly exceeded 80 mph on express runs. The famous "Flying Scotsman" service between London and Edinburgh, launched in 1862, symbolized the new age of rapid long-distance travel.

Social Transformation: Democratizing Travel

Perhaps the most profound impact of Victorian railways was social. Before railways, long-distance travel was the preserve of the wealthy; by the 1870s, it had become accessible to almost everyone. The Railway Regulation Act of 1844 required companies to provide at least one daily train on each route with affordable "Parliamentary" fares of one penny per mile.

Thomas Cook, originally a Baptist minister, saw the potential to organize excursions for temperance supporters in 1841. His business evolved into the world's first travel agency, with Cook pioneering package holidays by rail to seaside resorts and beauty spots. Workers' excursion trains brought previously isolated communities into contact, broadening horizons and transforming expectations.

The railways also standardized time itself. Before railways, each town kept its own local time based on the sun. The need for accurate timetables led railways to adopt standardized "railway time" based on Greenwich Mean Time, which eventually became the official standard throughout Britain in 1880.

Railway Architecture and the Transformation of Cities

The Victorian railway age transformed Britain's built environment. Grand terminal stations like London's St Pancras and Paddington, Liverpool Lime Street, and Newcastle Central became civic cathedrals of the industrial age – showcases of engineering prowess and architectural ambition.

Railway companies built hotels beside their stations, created new suburbs along their lines, and funded public facilities to attract passengers. Areas like Crewe, Swindon, and York developed into major railway towns, their economies and identities shaped by the needs of the network. Meanwhile, less visible infrastructure – cuttings, embankments, viaducts, and tunnels – reshaped landscapes across Britain.

The Apogee of Steam

By the Edwardian era, the railway network reached its greatest extent, with over 20,000 miles of track threading through almost every corner of Britain. The larger companies operated like states within a state, employing hundreds of thousands of workers in jobs ranging from drivers and guards to clerks, porters, signalmen, and track maintenance crews.

Express passenger services reached new heights of luxury and speed. Glamorous named trains like the "Flying Scotsman," "Cornish Riviera Express," and "Brighton Belle" competed for prestige and passengers. Elegant dining cars served multi-course meals on fine china, and Pullman services offered unparalleled comfort for those who could afford first-class fares.

Freight operations, though less glamorous, formed the backbone of the railway business, moving coal, raw materials, manufactured goods, agricultural produce, and mail throughout the country. This vast logistics network underpinned Britain's industrial might and global trade dominance.

As the First World War approached, Britain's railways seemed an unshakeable institution – efficient, profitable, and essential to national life. But the conflict would mark the beginning of a new chapter in their history.

Part III: Trials, Tribulations and Transformations (1914-1994)

Railways at War: 1914-1918

The First World War placed unprecedented demands on Britain's railways. Under government control from 1914 to 1921, the network prioritized military movements, transporting troops, equipment, and supplies to ports for shipping to the Western Front. Passenger services were reduced, equipment maintenance deferred, and railway workers diverted to military service.

The war demonstrated both the strategic importance of railways and the potential benefits of coordinated operation. When peace returned, the government faced a dilemma: return to the pre-war system of competing companies, or create a more unified network?

The Grouping: Four Giants Emerge

The 1921 Railways Act attempted compromise. Rather than full nationalization, it consolidated the hundreds of surviving railway companies into four large regional organizations:

- The Great Western Railway (largely unchanged)

- The London, Midland and Scottish Railway (LMS)

- The London and North Eastern Railway (LNER)

- The Southern Railway

This "Grouping" took effect in 1923, creating what became known as the "Big Four." These companies continued to operate competitively but with greater efficiency and coordination. Each developed its own distinctive character, livery, and engineering traditions.

The interwar period saw significant technical innovation. The LNER's "Flying Scotsman" became the first locomotive officially recorded at 100 mph in 1934, while its streamlined "Mallard" set a world speed record for steam locomotives of 126 mph in 1938 – a record that stands to this day. The LMS pioneered diesel shunting locomotives, and the Southern Railway led electrification efforts in southeast England.

Yet railways faced growing competition from road transport. Bus services captured local passenger traffic, while lorries took an increasing share of freight. The economic depression of the 1930s further strained railway finances, leading to service cuts and deferred maintenance.

The Second World War and Nationalization

World War II again placed tremendous pressure on Britain's railways. The network faced not only the logistical challenges of wartime operation but also direct attack during the Blitz and later V-weapon campaigns. By 1945, the system was physically exhausted – tracks worn, locomotives overdue for retirement, stations damaged or destroyed.

The post-war Labour government, committed to creating a comprehensive welfare state, saw nationalization as the solution. The Transport Act 1947 brought the Big Four under public ownership, creating British Railways (later British Rail) on January 1, 1948. For the first time, Britain's railways operated as a single unified system under direct government control.

British Railways inherited a network designed for the Victorian era, heavily dependent on labor-intensive steam technology. The 1955 Modernization Plan aimed to transform this, investing £1.2 billion in diesel and electric traction, modern signaling, track improvements, and station rebuilding.

But modernization coincided with accelerating social changes. Car ownership exploded, new motorways diverted long-distance travelers from rail, and traditional industries that had generated bulk freight began to decline. The railways' financial situation deteriorated rapidly, with mounting deficits requiring increased government subsidy.

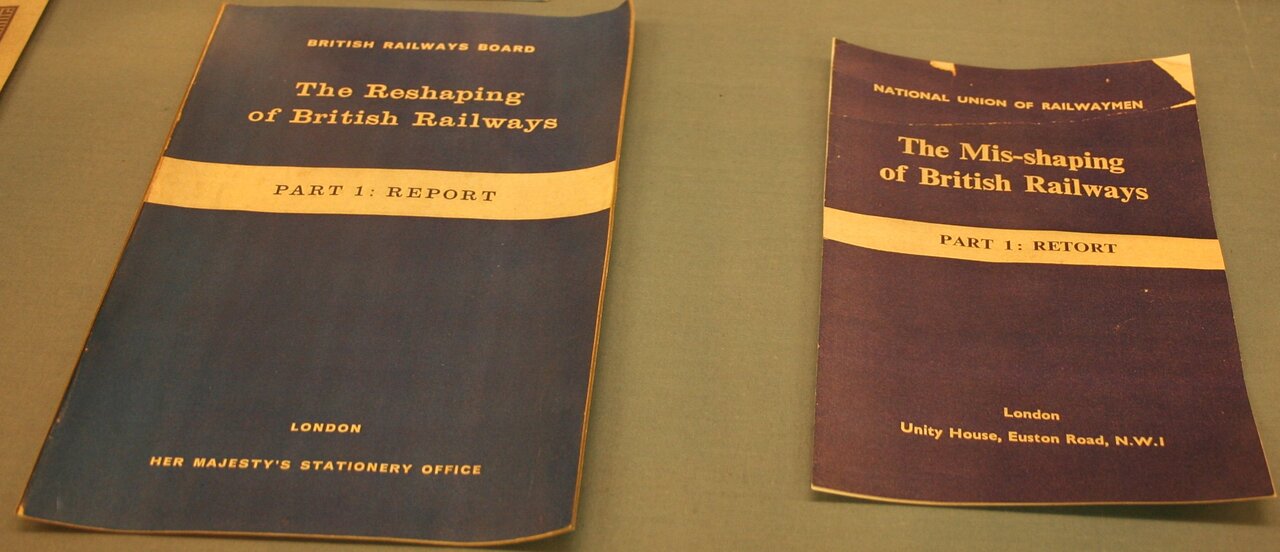

In 1963, Dr. Richard Beeching, chairman of the British Railways Board, published "The Reshaping of British Railways" – a report that would become infamous as the "Beeching Axe." He recommended the closure of 5,000 miles of track and over 2,000 stations that he deemed uneconomic, focusing resources on core trunk routes and freight services with growth potential.

The implementation of Beeching's recommendations transformed Britain's railway map. Branch lines serving rural communities disappeared, many market towns lost their railway connections entirely, and the network contracted to about half its former extent. While financially justifiable in narrow terms, these cuts had profound social consequences and have been controversial ever since.

British Rail: Reinvention and Innovation

Despite these contractions, the post-Beeching era saw significant innovation. The electrification of the West Coast Main Line was completed in 1974, allowing for 100+ mph services between London, Birmingham, Manchester, Liverpool, and Glasgow. In 1976, the High Speed Train (HST) or "InterCity 125" revolutionized long-distance travel with its 125 mph capability and distinctive aerodynamic design.

British Rail's iconic corporate identity, introduced in 1965, brought visual coherence to the network. The double-arrow logo, rail alphabet typeface, and consistent color schemes created a strong brand identity that remains recognizable decades later.

The organization was restructured several times, eventually settling in the 1980s on a sector-based approach with distinct businesses for InterCity (long-distance passenger), Network SouthEast (London commuter services), Regional Railways (provincial passenger services), and Railfreight.

Privatization: The End of British Rail

By the early 1990s, the political consensus that had supported nationalized industries was eroding. The Conservative government of John Major implemented the Railways Act 1993, which dissolved British Rail and created a complex new structure:

- Infrastructure ownership and maintenance transferred to Railtrack (later Network Rail)

- Passenger services divided among 25 train operating companies (TOCs) under franchise agreements

- Freight operations sold to private companies

- Rolling stock owned by three leasing companies (ROSCOs)

This controversial restructuring was completed by 1997, ending nearly 50 years of nationalized operation and creating one of the most complex railway systems in the world.

Part IV: The Modern Railway (1994-2025)

Growing Pains of Privatization

The early years of privatization brought mixed results. Passenger numbers, which had been declining or stagnant for decades, began to grow significantly – driven by economic growth, road congestion, and improved services on many routes. New trains were introduced, and some operators improved frequency and customer service.

However, the fragmented structure created coordination problems, and several high-profile accidents – including Southall (1997), Ladbroke Grove (1999), and Hatfield (2000) – raised serious safety concerns. Railtrack's focus on commercial property development over infrastructure maintenance came under intense criticism, especially after the Hatfield crash revealed severe rail deterioration across the network.

Following Hatfield, Railtrack imposed emergency speed restrictions across the network, causing nationwide service disruption. The company's financial position deteriorated rapidly, leading to its replacement in 2002 by Network Rail – a not-for-dividend company with greater public accountability, effectively renationalizing the infrastructure.

Renaissance and Record Growth

Despite these challenges, Britain's railways entered a period of unprecedented growth. Annual passenger journeys, which had fallen to 750 million by the early 1990s, surpassed their previous 1913 peak of 1.5 billion in 2015 and continued climbing to nearly 1.8 billion before the COVID-19 pandemic.

Major investment programs included:

- The West Coast Main Line upgrade, completed in 2008, allowing 125 mph operation throughout

- The Channel Tunnel Rail Link (High Speed 1), fully opened in 2007, bringing continental-style high-speed rail to Britain

- Thameslink Programme, expanding north-south connectivity through central London

- Crossrail (Elizabeth Line), creating a new east-west route across London

- Electrification of various mainlines, including the Great Western and Midland Main Lines

New rolling stock transformed passenger experiences, with air conditioning, Wi-Fi, power sockets, and improved accessibility becoming standard. The iconic HSTs were gradually replaced by new Intercity Express Programme trains, while commuter routes received new electric multiple units.

Structural Evolution

The privatized structure continued to evolve. Some early franchises failed financially and required government intervention. Franchise terms were repeatedly adjusted, generally becoming more prescriptive and less reliant on pure commercial incentives. Direct government involvement increased, particularly after the 2007-2008 financial crisis.

Following the controversial collapse of the East Coast franchise in 2018 (the third failure on this route), the British government began reconsidering the franchise model entirely. The Williams Rail Review, launched in 2018, recommended significant structural reforms, moving away from the classic franchise model toward a more unified system with greater public oversight.

The Pandemic and Beyond

The COVID-19 pandemic of 2020-2022 delivered the most severe shock to Britain's railways since World War II. Passenger numbers collapsed by over 95% during lockdowns, and the entire financial model of the privatized railway became unworkable overnight. The government was forced to suspend all franchise agreements, effectively renationalizing operations temporarily through Emergency Recovery Measures Agreements.

In 2021, the government announced the creation of Great British Railways – a new public body that will own infrastructure, collect fare revenue, run and plan the network, and set most fares and timetables. Train operators will continue to run most services, but as contracted service providers rather than commercial franchisees, ending the privatization experiment in its original form. The new Labour government, elected into power in 2024, has pledged largely to stick to this plan, except it will just outright nationalize the franchises as they expire and take all the lines into public ownership once again.

As Britain celebrates the bicentenary of railways in 2025, the network once again stands at a crossroads. Passenger numbers have recovered substantially from pandemic lows but remain below 2019 peaks, with changed travel patterns as remote working reduces traditional commuting. The environmental benefits of rail travel have gained new prominence in climate change discussions, while ambitious projects like HS2 (albeit in reduced form) point toward continued investment in rail infrastructure.

Two hundred years after the Stockton and Darlington Railway's first journey, Britain's railways continue to evolve, adapt, and serve as the backbone of the nation's transport system.

Part V: Experiencing Britain by Rail: A Traveler's Guide

Planning Your Journey: Tickets and Fares

For visitors to Britain, the railway system offers comprehensive coverage of the country but can seem bewilderingly complex. Here's what you need to know about tickets and fares:

Types of Tickets:

- Advance tickets: Cheapest option, available for specific trains booked ahead (typically 12 weeks before travel)

- Off-Peak and Super Off-Peak: Valid on less busy services, typically mid-day, evenings, and weekends

- Anytime tickets: Flexible tickets valid on any train on your chosen route, but considerably more expensive

- Season tickets: For regular travelers, offering unlimited travel on a specific route for periods from a week to a year

Money-Saving Options:

- Railcards: Various discount cards offering 1/3 off most fares, including the Two Together Railcard (for two named people traveling together), 16-25 Railcard, Senior Railcard (for those over 60), and Family & Friends Railcard

- Rover and Ranger tickets: Unlimited travel within specific regions for a set period

- BritRail passes: Available exclusively to overseas visitors before arrival in the UK, offering unlimited travel across Britain for various durations

Booking Tips:

- Book advance tickets as early as possible for the best prices, especially for long-distance journeys

- Consider split ticketing for longer journeys – sometimes buying separate tickets for different segments of your journey can be cheaper than a single through ticket

- Use fare comparison websites like Trainline, Rail Easy, or Loco2, but check the official National Rail website or train company sites before booking to avoid booking fees

- Remember that peak-time services (generally weekday mornings into major cities and evenings out) can be crowded and expensive – travel off-peak when possible

Navigating the Network

Britain's railway network connects most major towns and cities, with services operated by about 20 different train companies. Don't let this complexity deter you – the system functions as a unified network despite the different operators.

Key Routes and Services:

London and the Southeast: The densest part of the network, with frequent services and extensive commuter networks. Major London terminals include Euston, King's Cross, St Pancras, Paddington, Liverpool Street, Victoria, Waterloo, and London Bridge, each serving different regions.

InterCity Routes: High-speed, long-distance services connect London with major cities. Key routes include:

- West Coast Main Line (London Euston to Birmingham, Manchester, Liverpool, and Glasgow)

- East Coast Main Line (London King's Cross to Leeds, York, Newcastle, Edinburgh, and Aberdeen)

- Great Western Main Line (London Paddington to Bristol, Cardiff, and the West Country)

- Midland Main Line (London St Pancras to Sheffield and Nottingham)

Cross-Country Routes: Direct services between major cities without going through London, operated primarily by CrossCountry Trains, connecting Aberdeen, Glasgow, and Edinburgh in Scotland with cities like Newcastle, Manchester, Birmingham, Bristol, and Plymouth.

Regional and Rural Services: Slower, stopping services connecting smaller towns and communities, often using single-track lines and with less frequent schedules.

Planning Tools:

- The National Rail website and app provide comprehensive timetable information, live updates, and journey planning

- Trainline and other third-party apps offer similar functionality, often with additional features

- Google Maps can be useful for basic journey planning, especially for understanding connections with other transport modes

Station Facilities:

Larger stations typically offer:

- Ticket offices and automatic ticket machines

- Shops, cafes, and restaurants

- Left luggage facilities

- Waiting rooms

- Toilet facilities (usually requiring a small fee)

- Information desks and departure boards

Smaller stations may have limited facilities, with some unstaffed altogether, so plan accordingly.

Practical Rail Travel Tips

Before Your Journey:

- Arrive at least 15 minutes before departure for regional services, and 30 minutes for long-distance trains

- Download the National Rail app for real-time updates on delays or disruptions

- Consider reserving seats (free with most advance tickets) for long-distance journeys, especially during peak travel periods and holidays

- Familiarize yourself with the bicycle policy if planning to travel with a bike – rules vary by operator and route, and space is often limited

On Board:

- British trains do not have formal check-in procedures – you simply board with your ticket, which will be checked during the journey

- Most long-distance services have trolley catering or a cafe car, but quality varies – consider bringing your own refreshments

- Many trains now offer Wi-Fi, though connectivity can be patchy in rural areas

- Quiet coaches are available on many long-distance services for those seeking a more peaceful journey

- Pay attention to station announcements, as platforms can sometimes change at short notice

Regional Differences:

- Scotland: ScotRail operates most services within Scotland, with some spectacular scenic routes through the Highlands

- Wales: Transport for Wales operates most services within Wales, including the scenic Heart of Wales and Cambrian Coast lines

- Northern England: Northern and TransPennine Express operate most regional services, connecting cities like Manchester, Leeds, Liverpool, and Newcastle

- Southwest England: Great Western Railway serves Devon and Cornwall, including the stunning coastal route through Dawlish

Accessibility:

- Most major stations are now fully accessible, with lifts or ramps to platforms

- Assistance for disabled passengers can be arranged through the Passenger Assist service, ideally 24 hours in advance

- Most modern trains have dedicated spaces for wheelchair users and accessible toilets

Iconic Railway Journeys

Britain offers some of the world's most scenic railway journeys. Consider including these routes in your itinerary:

West Highland Line (Glasgow to Mallaig)

Often voted among the world's most beautiful rail journeys, this line passes through remote Highland scenery, across the Glenfinnan Viaduct (featured in Harry Potter films), and along the shores of lochs and the sea coast.

Settle-Carlisle Line

This engineering marvel cuts through the Yorkshire Dales and North Pennines, featuring 20 viaducts and 14 tunnels. The highlight is the quarter-mile-long Ribblehead Viaduct with its 24 massive stone arches.

Cambrian Coast Line (Machynlleth to Pwllheli)

Hugging the coast of Cardigan Bay in Wales, this route offers spectacular views of beaches, cliffs, and distant mountains, passing through charming seaside towns.

Durham Coast Line (Newcastle to Middlesbrough)

Less well-known but dramatically beautiful, this line runs along the cliff tops of northeastern England, with sweeping views of the North Sea.

Cornish Main Line (Plymouth to Penzance)

Crossing Brunel's Royal Albert Bridge before running close to the south coast of Cornwall, with views of sandy beaches, fishing villages, and lush estuaries.

Kyle Line (Inverness to Kyle of Lochalsh)

Crossing Scotland from east to west, this line passes through magnificent Highland landscapes before reaching the shores opposite the Isle of Skye.

Part VI: Heritage Railways: Preserving Steam's Golden Age

The Preservation Movement

As British Railways modernized in the 1950s and 1960s, steam locomotives were gradually withdrawn from service, with the last regular steam service on the national network running in August 1968. This might have marked the end of Britain's steam heritage, but for a remarkable grassroots preservation movement.

Rail enthusiasts, local communities, and volunteers came together to save lines threatened with closure or already closed, preserving not just the physical infrastructure but the skills, traditions, and experience of the steam age. Today, over 100 heritage railways operate across Britain, ranging from short tourist lines to substantial operations running genuine transport services.

Major Heritage Railways

Britain's heritage railways offer visitors the chance to experience rail travel as it was in the golden age of steam. Here are some of the most significant:

North Yorkshire Moors Railway

Running 18 miles through the spectacular scenery of the North York Moors National Park from Pickering to Whitby, this is one of Britain's longest and most popular heritage lines. It featured as "Hogsmeade Station" in the Harry Potter films.

Severn Valley Railway

Operating 16 miles between Kidderminster and Bridgnorth, this preserved GWR line follows the River Severn through picturesque countryside. It boasts an impressive collection of locomotives and rolling stock.

Bluebell Railway

The first standard gauge preserved line in Britain, opened in 1960, the Bluebell runs through the beautiful Sussex countryside. It features meticulously restored Victorian stations and an impressive collection of Southern Railway locomotives.

Ffestiniog and Welsh Highland Railways

These narrow gauge lines in Snowdonia, North Wales, offer some of the most spectacular mountain railway journeys in Britain. The Ffestiniog Railway is the oldest independent railway company in the world, founded in 1832.

West Somerset Railway

The longest standard gauge heritage railway in Britain at 20 miles, running through the Quantock Hills and along the Bristol Channel coast from Bishops Lydeard to Minehead.

Keighley and Worth Valley Railway

Famous as the setting for the film "The Railway Children," this 5-mile branch line in Yorkshire runs through Brontë Country from Keighley to Oxenhope.

Bo'ness and Kinneil Railway

Scotland's largest heritage railway, located near Edinburgh, offering views across the Firth of Forth and home to the Scottish Railway Preservation Society.

Special Events and Experiences

Heritage railways offer more than just standard service trains:

Galas and Special Events: Many lines hold steam galas featuring visiting locomotives, increased service frequency, and special demonstrations.

Dining Experiences: From full-service dining trains to fish and chip specials and afternoon tea services, heritage railways often combine gastronomy with rail travel.

Driver Experience Courses: Several railways offer the chance to fulfill a childhood dream by learning to drive a steam locomotive under expert supervision.

Santa Specials: During the Christmas season, many heritage railways run special services with seasonal decorations and a visit from Father Christmas.

Photography Charters: Dedicated events for railway photographers, often featuring historic locomotives and rolling stock in authentic settings.

Behind the Scenes

Most heritage railways rely heavily on volunteers, who perform roles ranging from locomotive maintenance to station staffing, track maintenance, catering, and administration. These dedicated enthusiasts ensure that traditional railway skills remain alive for future generations.

Many lines also have educational programs, working with schools to teach children about steam power, industrial history, and the social impact of railways. Museums and exhibition spaces at major heritage railways provide deeper insight into railway history and technology.

For the railway enthusiast, heritage lines offer unparalleled opportunities to see historic locomotives in action, often in the landscapes they were designed to serve. From tiny industrial shunting engines to mighty express locomotives, the heritage sector preserves examples of most significant British steam designs.

Part VII: The Future of Britain's Railways

Current Challenges and Opportunities

As Britain's railways enter their third century, they face a complex mix of challenges and opportunities:

Post-Pandemic Recovery: Adapting to changed travel patterns following COVID-19, with reduced commuting but potential growth in leisure travel.

Climate Change Imperatives: Railways offer significant environmental advantages over road and air travel, positioning them as a key element in decarbonization strategies.

Infrastructure Renewal: Much of Britain's railway infrastructure dates from the Victorian era and requires substantial investment to maintain and improve.

Capacity Constraints: Despite network contractions, many routes operate at or near capacity during peak periods, limiting growth potential without major infrastructure investment.

Technological Evolution: Developments in digital signaling, hydrogen and battery propulsion, and autonomous operation promise to transform railway operations.

Major Projects and Proposals

Several significant projects are reshaping Britain's railways:

High Speed 2 (HS2): The controversial new high-speed line is under construction between London and Birmingham, with potential future extensions to Manchester. Though scaled back from original plans, it represents the largest new railway project in Britain for over a century.

Great British Railways: This new public body will integrate the fragmented railway system under stronger public control while nationalizing ownership.

Digital Railway Programme: A comprehensive plan to replace traditional signaling with digital systems, potentially increasing capacity on existing lines by 40%.

Restoring Your Railway: An initiative to reverse some of the Beeching cuts, reopening closed lines where they can deliver economic and social benefits.

Electrification: Ongoing programs to extend electrification across the network, reducing diesel operation and improving environmental performance.

The Next 200 Years?

As Britain commemorates two centuries of railway history, it's worth considering what the next 200 years might bring. High-speed lines might eventually connect all major cities. Automated operation could transform economics and safety. Magnetic levitation or evacuated tube transport might supplement or replace conventional rail technology.

Whatever technological changes occur, the fundamental advantages of railways remain: efficient use of land, energy efficiency, and the ability to move large numbers of people and goods safely and reliably. The railway revolution that began in northeast England in 1825 continues to evolve, adapt, and shape Britain's landscape, economy, and society.

Conclusion: 200 Years and Counting

Two centuries after Stephenson's "Locomotion No. 1" made its historic journey, Britain's railways have been transformed almost beyond recognition – yet their essential purpose remains unchanged. They continue to connect communities, transport goods, and enable personal mobility while adapting to changing social needs and technological possibilities.

As we celebrate this bicentenary, we honor not just an engineering achievement but a force that has fundamentally shaped modern Britain. The railway story encompasses technological innovation, social transformation, economic development, and cultural change. It reflects the nation's industrial might, its social priorities, its economic philosophies, and its relationship with its own landscape.

From humble beginnings hauling coal in the northeast to today's complex network carrying millions of passengers daily, Britain's railways have weathered wars, economic crises, political upheavals, and technological revolutions. They have been privately owned, nationalized, privatized, and now exist in a hybrid state reflecting contemporary pragmatism over ideological purity.

The 200th anniversary offers an opportunity not just to look back with nostalgia but forward with purpose. Railways remain as relevant to Britain's future as they were to its past – perhaps even more so as environmental concerns move center stage. Their ability to transport large numbers of people and goods efficiently and with minimal environmental impact positions them as a transport mode for the sustainable future.

For the traveler, Britain's railways continue to offer one of the finest ways to experience the country – from bustling cities to remote rural landscapes, from coastal vistas to mountain passes. The network that transformed the nation now invites visitors to discover that nation in all its diversity and beauty.

The clickety-clack of wheels against track, the distant whistle echoing across green valleys – these sounds may have evolved with modern technology, but the essential magic of railway travel endures. As Britain's railways embark on their third century, they carry forward not just passengers and freight but a remarkable legacy and the promise of journeys yet to come.

_Head_of_Steam,_Darlington_30.06.2009_P6300119_(10192855826).jpg)

_The_Railway_Station_colorized.jpg)

Post a reply