Sunday Post: Communing With Thomas Hardy at His Birthplace in Dorset

This week, we're taking you on a literary pilgrimage to one of England's most evocative historic sites – the humble cottage where Thomas Hardy was born and raised. In our featured article, I share my deeply personal journey to this National Trust treasure nestled in the heart of Dorset's countryside. Whether you're a devoted Hardy enthusiast or simply appreciate the connection between place and literary genius, you'll discover how this modest thatched dwelling shaped one of Britain's greatest writers and how it continues to cast its spell on visitors today. Join us as we step through the doorway where Hardy's Wessex was born, in a landscape that remains remarkably unchanged since he immortalized it in his beloved novels.

Member Update

We're now back up to 176 members! Welcome to everyone who joined this week! Thank you! We also have an exciting update for the podcast, it should finally return to a weekly release schedule this week. We recorded three episodes last week, and have more scheduled. So, hopefully going forward the weekly early releases will resume. We're also working on some 'upgrades' to the podcast - stay tuned for what exactly that means!

Here are some highlights from the chat community this week:

- Lockerbie - The Search for Truth

- Wallace & Gromit: Vengeance Most Fowl Reaction Thread

- PBS Unveils First Look at Miss Austen

- Bridget Jones Mad About the Boy Discussion Thread

- Is Anyone Considering Moving to the UK?

- Paddington in Peru Reaction Threads

Sunday Post: Communing With Thomas Hardy

My love for Dorset goes hand in hand with my love of the literary works of Thomas Hardy, a man more associated with Dorset than any other. His novels—from Far from the Madding Crowd to Tess of the d'Urbervilles—capture the essence of this remarkable county, transforming its rolling hills, ancient heaths, and pastoral valleys into the semi-fictional "Wessex" that has become as real to his readers as the actual landscape itself.

For years, visiting his birthplace nestled deep in the Dorset countryside had been a personal pilgrimage I longed to make—not just because of its connection to the literary giant, but also because I'd heard tales of its stunning setting, a landscape that had shaped one of England's most distinctive literary voices. I wanted to see for myself the views that inspired his poetic descriptions, to walk the paths he walked, and perhaps to understand better how this environment influenced his unique perspective on rural life, social convention, and the inexorable march of modernity.

Despite countless trips to Dorset over the years, I had somehow never managed to visit Hardy's birthplace. It was either closed for the season or couldn't fit into an itinerary filled with family commitments and other attractions. Each time I found myself in Dorset—whether walking along the Jurassic Coast, exploring the market towns, or admiring ancient hill forts—I felt a pang of regret at not having made the journey to where it all began for Hardy.

Then, about ten years ago, after a delightful afternoon exploring the grand National Trust property at Kingston Lacey nearby with its impressive art collection and beautiful gardens, my wife and I found ourselves with a couple of hours free on a beautiful spring afternoon. The weather was perfect—clear blue skies with just enough of a breeze to rustle the new leaves—and with no children in tow and the day still bright with promise, we made an impulsive decision. We would finally make that pilgrimage to Hardy's birthplace.

I was particularly excited to visit the newly completed visitor center I'd read about. The National Trust, and the local county authority, had recently invested in creating a modern, informative gateway to the Hardy experience, promising interactive displays and context that would enrich the visit to the cottage itself. With the GPS guiding us through the winding Dorset lanes, we made our way toward Higher Bockhampton, racing against the clock.

We arrived just in time for the last entry of the day, slightly breathless but exhilarated at having finally made it to this long-anticipated literary shrine.

The modern visitor center, with its sleek design and informative displays, provided a stark contrast to what awaited us beyond. After a quick introduction from the friendly National Trust staff, we set off down the woodland path that leads to the cottage. This approach to Hardy's birthplace is an experience in itself—a gentle transition from our modern world to Hardy's.

The path winds through Thorncombe Wood, a remnant of ancient woodland that Hardy would have intimately known as a child. In early spring, the forest floor was carpeted with the first wildflowers of the season—wood anemones, celandines, and early bluebells creating splashes of color among the leaf litter. Birdsong accompanied our walk, and shafts of late afternoon sunlight filtered through the canopy of oak, ash, and beech trees, many of which would have stood during Hardy's lifetime.

Then, just as I was settling into the rhythm of the forest, the trees suddenly gave way, and there—standing before us like a vision from another time—was the cottage. The immediate impact was visceral. It sits so perfectly in its landscape that you could almost be looking at a Turner or Constable painting come to life. In that moment of first glimpse, it feels almost unreal, a physical manifestation of Hardy's literary world stepped straight from the pages of his novels.

The cottage is everything an admirer of Hardy could hope for—modestly proportioned yet dignified, its walls bright against the green backdrop, and its thatched roof golden in the spring sunshine. A small, well-tended garden surrounded the building, with traditional cottage plants that would have been familiar to the Hardy family: herbs, vegetables, and the sorts of simple flowers that adorn country gardens. A low stone wall encircles the property, creating a boundary between the domestic sphere and the wild heath beyond—a physical embodiment of the tension between civilization and nature that runs through so much of Hardy's work.

Built of cob and brick under a thatch roof in 1800 by Hardy's grandfather, this humble dwelling is where the celebrated author and poet was born in 1840. The cottage sits within what was once part of the ancient Egdon Heath, a landscape that would later feature prominently in his novels, most notably in "The Return of the Native." Standing there, looking from the cottage to the surrounding countryside, I could almost hear the opening lines of that novel echoing in my mind: "A face on which time makes but little impression is the face of the great Egdon Heath..."

The surrounding woodland of Thorncombe Wood and what was once Puddletown Heath provided endless inspiration for the young writer, with its ancient trees, winding paths, and seasonal transformations becoming deeply embedded in his consciousness and his work. Hardy's keen observations of this environment—its weather patterns, its flora and fauna, its changing colors through the seasons—would inform the richly detailed descriptions that make his novels so immersive. For Hardy, landscape was never merely backdrop but a living presence, almost a character in itself, shaping the lives and fates of his human protagonists.

With a sense of reverence that surprised even myself, I ducked my head (the doorway is quite low, typical of cottages of this period) and stepped across the threshold. Immediately, the atmosphere changed. The air inside was cooler, with that distinctive smell that old buildings have—a blend of woodsmoke from the fireplace, aged timber, and the subtle mustiness of history (often mold, but I digress). The cottage is remarkably small by modern standards, yet it housed the Hardy family of six. Thomas shared this space with his parents Thomas Sr. and Jemima, his brother Henry, and his two sisters Mary and Kate.

The limited space would have necessitated a close-knit family life, with little room for privacy—a reality that perhaps contributed to Hardy's acute observations of family dynamics and the complex interplay of personalities in confined rural communities. It made me think of the cramped cottages in his novels, like the Durbeyfields' home in Tess or the Woodlanders' dwellings, where proximity breeds both intimacy and conflict.

What struck me most was how meticulously the National Trust has preserved the cottage much as it would have been during Hardy's childhood. The simple furnishings reflect the rural working-class background of his family, creating an intimate connection to the author's beginnings. There is nothing fancy here—sturdy wooden furniture, homespun textiles, and practical household implements. Yet there's a dignity to the simplicity, a sense of pride in modest but comfortable surroundings that reflects the status of Hardy's family as skilled craftspeople rather than laborers.

In the kitchen, with its central hearth and iron cooking implements, I imagined Mrs. Hardy preparing meals while young Thomas observed, absorbing the rhythms and routines of rural domestic life that would later feature so prominently in his novels. A National Trust volunteer pointed out various authentic items—from butter paddles to bread ovens—explaining their functions and how they connected to daily life in Hardy's time.

The small parlor where Hardy was educated by his mother Jemima—a well-read woman who encouraged young Thomas's love of literature—feels charged with the beginning of literary greatness. It was here that he would have first encountered classic works and local folk tales alike, developing the narrative sensibility that would make him one of England's greatest storytellers. The room contains a few books similar to those the family might have owned, including a Bible and some volumes of Shakespeare—the twin pillars of literary influence in the Victorian era.

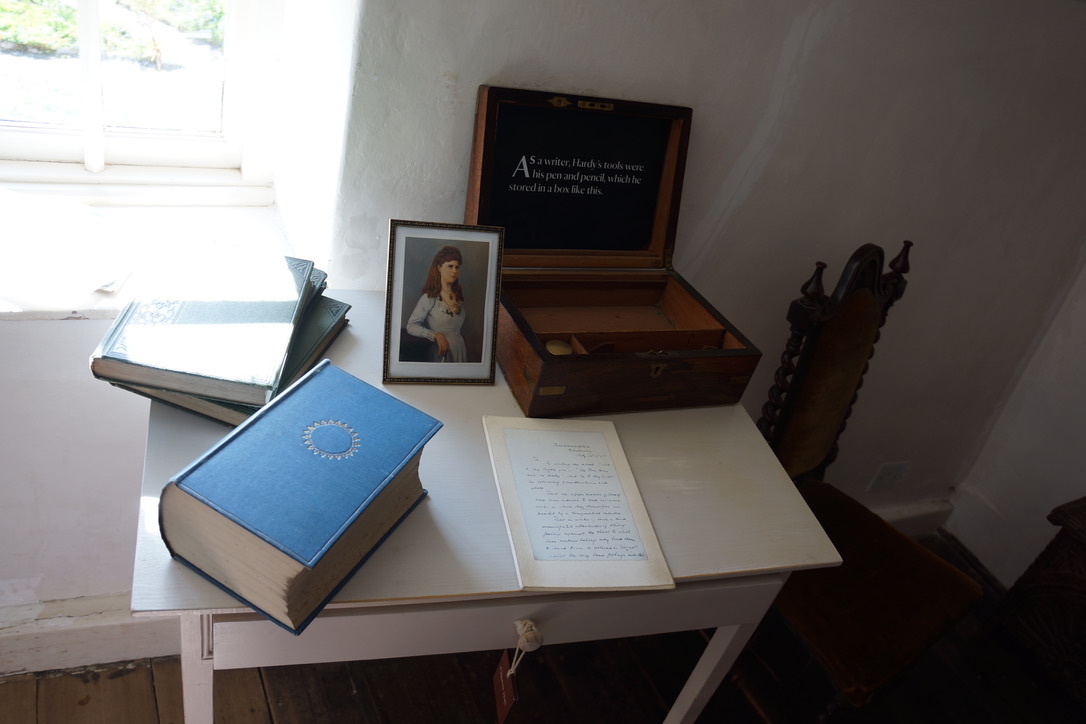

The highlight of the tour for me, however, was ascending the narrow, creaking staircase to the small upstairs bedroom that served as Hardy's study in his young adulthood. It was here that he wrote "Under the Greenwood Tree" and "Far from the Madding Crowd," works that established his literary reputation and set him on the path to becoming the voice of rural Wessex. Standing in this modest space was a profoundly moving experience for me as a Hardy enthusiast. The room is sparsely furnished—just a bed, a chair, and a writing table positioned to catch the natural light from the small window.

It's such a simple, modest space—the perfect place for writing, free from distraction yet with a view of the natural world that so inspired him. I found myself standing quietly, almost holding my breath, imagining him at his simple desk (though I learned that the actual desk is preserved in the nearby Dorset Museum in Dorchester), gazing out at the gardens, crafting his tales of country drama in late-Victorian England. Perhaps he sat here watching the changing light across the heath, listening to the birds and the wind in the trees, and finding in these ordinary sensations the extraordinary inspiration for his art.

For a lover of his works, it was an electric moment to be in the very space where some of my favorite stories first took form. I thought of the characters who had been born in this room—the spirited Bathsheba Everdene, the steadfast Gabriel Oak, the entire community of Mellstock with its choir and its traditions. They seemed almost palpable in that quiet, timeless space, as if I might turn and find them standing beside me, Hardy's imagination having granted them a reality that transcends the page.

As we continued our exploration, I found myself running my hand along the interior walls, feeling the slight irregularities of the cottage's construction beneath the whitewash. The knowledgeable National Trust guide explained that the building exemplifies traditional Dorset building techniques that Hardy would later describe with such precision in his novels. The thick cob walls—a mixture of clay, straw, and local materials—provided natural insulation against the harsh Dorset winters, keeping the interior cool in summer and relatively warm in winter.

The guide pointed out various details that revealed the skill of the original builders—the sturdy oak beams supporting the ceiling, the carefully crafted window frames, the flagstone floor worn smooth by generations of family feet. I was particularly fascinated by the construction of the fireplace, the heart of the home in Hardy's time, designed to maximize heat while minimizing the risk of fire to the thatched roof above.

Speaking of that thatched roof, I learned that it requires regular maintenance and replacement, typically every 25-30 years, using traditional methods. The current thatch, golden and aromatic, was still relatively new when we visited, having been recently replaced by one of the few master thatchers still practicing in Dorset. This craft, like so many traditional skills, has become increasingly rare in our modern world, making the preservation of buildings like Hardy's Cottage all the more important as living museums of vernacular architecture and craftsmanship.

What's remarkable about the cottage is how well it demonstrates the sustainable building practices of pre-industrial England. Nearly everything used in its construction would have been sourced locally—the clay and straw for the cob walls, the stone for the foundations, the oak for the beams, and the water reed or wheat straw for the thatch. This connection to the local landscape, this embeddedness in the natural world, is something Hardy clearly valued and mourned as it began to disappear during his lifetime with the advance of industrialization and standardization.

The cottage stands as a testament to the craftsmanship of rural builders and their sustainable use of local materials before the industrial age transformed construction methods. That it stands today, preserved through traditional methods, ensures these valuable old crafts aren't lost to time. In an age of mass production and global supply chains, there's something profoundly appealing about a home built entirely from materials found within a few miles of its location, by craftspeople whose skills were passed down through generations.

I couldn't help but think of passages in Hardy's novels where he describes rural dwellings with such intimate knowledge—from the leaky roof of Marty South's cottage in The Woodlanders to the ancient farmhouse of Weatherbury in Far from the Madding Crowd. His detailed descriptions of these buildings reveal not just an aesthetic appreciation but a deep understanding of their construction and function, knowledge surely gained from growing up in this very cottage and observing the ongoing process of its maintenance and repair.

As I stood in the garden, gazing back at the cottage in the golden late afternoon light, I found myself wondering about its journey through time—how it had survived to become the literary shrine I was now visiting. The story of what happened to the cottage after Hardy achieved fame adds another fascinating layer to its history.

Following his departure in the 1870s to establish himself in his self-designed home Max Gate (also now owned by the National Trust and well worth a visit), the cottage continued to be occupied by his family. His father, Thomas Hardy Sr.—a master mason and builder whose craft had supported the family—lived here until his death in 1892. His mother Jemima, who had been such a formative influence on his education and literary interests, remained in the cottage until her death in 1904.

There's something quite poignant about that continuity. Even as Hardy's literary fame grew, as he dined with the cultural elite of London and received acclaim from around the world, his parents continued their modest rural life in the cottage where he had been born. This connection to his roots remained important to Hardy throughout his life. He visited regularly, and the cottage appears in various forms in his fiction, most notably as the home of the Stokes family in his short story "The Withered Arm."

After the deaths of Hardy's parents, the cottage passed to his sister Kate, who maintained it until her death in 1940. Kate was herself an interesting character—independent, unmarried, and devoted to preserving her brother's legacy. Throughout this period, as Hardy's literary reputation solidified and his works became classics of English literature, the cottage began attracting literary pilgrims from around the world.

Kate, recognizing the historical significance of her childhood home and perhaps feeling the weight of responsibility as the last Hardy to occupy it, preserved many features as they had been during her brother's early years. She welcomed visitors, shared stories about her famous brother, and inadvertently began the transformation of the cottage from family home to literary heritage site. In a sense, she was the first curator of what would eventually become a museum.

Our National Trust guide shared the fascinating detail that during Kate's tenure, visitors included literary luminaries such as T.E. Lawrence (Lawrence of Arabia) and the poet Robert Graves, both admirers of Hardy's work who made the pilgrimage to see where their literary hero had begun his journey.

Following Kate's death in 1940, the cottage faced an uncertain future during the tumultuous years of World War II. With no direct Hardy descendants to inherit it, there was genuine concern that this important literary landmark might be sold for private use or even demolished to make way for more modern housing. The war years were a particularly vulnerable time for heritage properties, with many country houses and historic buildings requisitioned for military use or allowed to fall into disrepair as resources were directed toward the war effort.

Recognizing the cultural significance of the cottage, a group of Hardy enthusiasts, literary scholars, and local preservationists campaigned to save it for the nation. Their efforts culminated in 1948 when the National Trust acquired the property, ensuring its protection for future generations. The campaign to save Hardy's birthplace was part of a broader movement in post-war Britain to preserve the nation's cultural heritage, seeing in these historic sites a connection to national identity that many felt was important to maintain in the face of rapid social change.

The Trust's acquisition of the cottage was not just about preserving the physical structure but about maintaining a connection to Hardy's literary legacy and the rural way of life he had documented so meticulously in his novels and poetry—a way of life that was rapidly disappearing in the wake of mechanization, urbanization, and the social changes accelerated by two world wars.

As we completed our tour of the interior, our guide shared a fascinating piece of behind-the-scenes information that delighted me as a Hardy enthusiast with an interest in preservation. My favorite bit of trivia about the cottage is that there is actually a small apartment upstairs where a caretaker lives to keep an eye on the property. This living presence in the historic building provides security, allows for immediate response to any issues like leaks or other potential damage, and maintains a continuity of occupation that feels appropriate for a family home. The guide mentioned that at one point, this caretaker was an American—a Hardy scholar who had fallen in love with the author's work and Dorset itself, and who considered the opportunity to live in Hardy's birthplace an unparalleled honor.

This human connection to the cottage reinforces something I felt strongly during my visit—that Hardy's birthplace is not simply a static museum but a living heritage site, one that continues to inspire and engage with each new generation of visitors. The National Trust has done a remarkable job of balancing preservation with accessibility, creating an experience that feels both authentic and engaging.

Today, Hardy's Cottage serves as both museum and literary pilgrimage site for visitors from around the world. The Trust has created an engaging visitor experience that combines historical authenticity with thoughtful interpretation. Traditional conservation techniques ensure that the physical structure remains sound while preserving its historical character. The interior displays are refreshed periodically to highlight different aspects of Hardy's life and work, ensuring that repeat visitors find something new to discover.

Visitors can see period furnishings carefully researched to match what would have been present during Hardy's youth, household items that demonstrate the daily routines of rural life in Victorian Dorset, and reproductions of Hardy's manuscripts and early editions of his works. Personal artifacts—some original to the family, others representative of the period—provide a multifaceted view of both his domestic life and creative process.

After exploring the cottage interior thoroughly, we stepped back into the garden to absorb the atmosphere of the place in its entirety. What makes the visit so special—and what I'll always remember most vividly—is the profound sense of peace that envelops the place. We had arrived in the late afternoon and were the last visitors admitted, so we practically had the place to ourselves as the day began its gentle transition toward evening.

What struck me most was the quality of the silence—not an absence of sound but a different kind of soundscape altogether from our usual urban experience. The only sounds were those of nature in early spring: the rustle of leaves in the light breeze, the occasional call of a bird returning to roost, the distant lowing of cattle from a neighboring farm. There was none of the constant background noise we've become so accustomed to in modern life—no traffic, no machinery, no electronic hum—just the sounds that Hardy himself would have heard as he sat writing or walked these paths in contemplation.

The cottage is surrounded by carefully tended gardens that blend seamlessly into the woodlands beyond, creating a peaceful, inspirational atmosphere that feels largely unchanged from Hardy's time. We strolled slowly around the perimeter, pausing to admire the early spring flowers beginning to bloom in the borders—primroses, daffodils, and the first tender shoots of plants that would flower later in the season. A gnarled apple tree, possibly old enough to have been there in Hardy's time, stood sentinel at one corner of the garden, its twisted branches just beginning to show the promise of new growth.

The light was magical at this hour, the low sun casting long shadows across the garden and illuminating the cottage with a warm, golden glow that seemed to bring the whitewashed walls alive. I tried to capture this quality in photographs, but none quite conveyed the tranquil beauty of the moment—that peculiar combination of natural beauty, historical resonance, and personal connection that makes certain places feel almost sacred.

As the afternoon light began to soften further, we reluctantly took our leave, walking back through the hamlet of Higher Bockhampton toward where we had parked our car. It was a lovely stroll—quiet, with spring flowers blooming in the hedgerows and charming Dorset cottages lining the narrow lane. Some of these cottages, though modernized inside, would have been standing when Hardy was a boy, part of the community that formed his earliest social world.

You can see exactly what the Hardy family saw in this place—its natural beauty, its sheltered position, its connection to both the wild heath and the cultivated landscape. I'm happy to report that it still maintains its rural character—just as Hardy would have wanted. Despite the pressures of development that have transformed so much of the English countryside, this corner of Dorset seems suspended in time, protected both by formal conservation measures and by the respect that locals and visitors alike have for its literary associations.

For literary scholars and enthusiasts alike, the cottage represents the starting point of Hardy's "Wessex," the semi-fictional region he created as the setting for his novels. By beginning at the cottage and exploring the surrounding countryside, visitors can trace the connections between the real Dorset landscape and Hardy's imaginative transformation of it into one of literature's most fully realized fictional worlds. You can stand on the edge of what was once Egdon Heath and understand viscerally the power of that landscape as Hardy described it: "It was at present a place perfectly accordant with man's nature—neither ghastly, hateful, nor ugly; neither commonplace, unmeaning, nor tame; but, like man, slighted and enduring; and withal singularly colossal and mysterious in its swarthy monotony."

The enduring appeal of Hardy's Cottage lies in its authenticity and its power to connect visitors directly with the origins of Hardy's artistic vision. In this humble dwelling, surrounded by the timeless beauty of the Dorset countryside, one of England's greatest writers found the foundation for a body of work that continues to resonate with readers more than a century after it was written. The universal themes he explored—the relationship between humans and their environment, the tension between tradition and progress, the role of chance and circumstance in shaping individual destinies—all were formed here, in this specific place, through his observations of this particular community and landscape.

For anyone who has fallen under the spell of Hardy's prose, standing where it all began is nothing short of magical. The visit deepened my appreciation for his work, adding layers of understanding that no academic study could provide. I left with a renewed desire to revisit his novels, to trace the connections between the real places I had seen and their fictional counterparts, to appreciate anew the precision of his descriptions and the depth of his connection to this landscape.

As we drove away through the gathering dusk, I felt a sense of gratitude—to Hardy for the enduring gift of his work, to his family for preserving his birthplace during their lifetimes, to the campaigners who saved it after Kate's death, to the National Trust for their careful stewardship, and to all those who recognize the importance of maintaining these connections to our literary heritage. In a rapidly changing world, such places of continuity and contemplation become ever more precious.

I vowed not to let another decade pass before returning to this special place—perhaps in a different season, to experience the cottage and its surroundings in another of their many moods. Until then, I would carry with me the memory of that golden afternoon light on brick walls, thatched roof, and the profound silence of a place where one of our greatest literary voices first learned to observe and to speak.

Post a reply